Portal:Minerals

Portal maintenance status: (May 2019)

|

The Minerals Portal

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.

The geological definition of mineral normally excludes compounds that occur only in living organisms. However, some minerals are often biogenic (such as calcite) or organic compounds in the sense of chemistry (such as mellite). Moreover, living organisms often synthesize inorganic minerals (such as hydroxylapatite) that also occur in rocks.

The concept of mineral is distinct from rock, which is any bulk solid geologic material that is relatively homogeneous at a large enough scale. A rock may consist of one type of mineral or may be an aggregate of two or more different types of minerals, spacially segregated into distinct phases.

Some natural solid substances without a definite crystalline structure, such as opal or obsidian, are more properly called mineraloids. If a chemical compound occurs naturally with different crystal structures, each structure is considered a different mineral species. Thus, for example, quartz and stishovite are two different minerals consisting of the same compound, silicon dioxide. (Full article...)

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization. (Full article...)

Selected articles

-

Image 1Galena with minor pyrite

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crystallizes in the cubic crystal system often showing octahedral forms. It is often associated with the minerals sphalerite, calcite and fluorite.

As a pure specimen held in the hand, under standard temperature and pressure, galena is insoluble in water and so is almost non-toxic. Handling galena under these specific conditions (such as in a museum or as part of geology instruction) poses practically no risk; however, as lead(II) sulfide is reasonably reactive in a variety of environments, it can be highly toxic if swallowed or inhaled, particularly under prolonged or repeated exposure. (Full article...) -

Image 2

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ion, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common endmembers is written as Ca10(PO4)6(OH,F,Cl)2, and the crystal unit cell formulae of the individual minerals are written as Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, Ca10(PO4)6F2 and Ca10(PO4)6Cl2.

The mineral was named apatite by the German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner in 1786, although the specific mineral he had described was reclassified as fluorapatite in 1860 by the German mineralogist Karl Friedrich August Rammelsberg. Apatite is often mistaken for other minerals. This tendency is reflected in the mineral's name, which is derived from the Greek word ἀπατάω (apatáō), which means to deceive. (Full article...) -

Image 3

Corundum is a crystalline form of aluminium oxide (Al2O3) typically containing traces of iron, titanium, vanadium, and chromium. It is a rock-forming mineral. It is a naturally transparent material, but can have different colors depending on the presence of transition metal impurities in its crystalline structure. Corundum has two primary gem varieties: ruby and sapphire. Rubies are red due to the presence of chromium, and sapphires exhibit a range of colors depending on what transition metal is present. A rare type of sapphire, padparadscha sapphire, is pink-orange.

The name "corundum" is derived from the Tamil-Dravidian word kurundam (ruby-sapphire) (appearing in Sanskrit as kuruvinda).

Because of corundum's hardness (pure corundum is defined to have 9.0 on the Mohs scale), it can scratch almost all other minerals. Emery, a variety of corundum with no value as a gemstone, is commonly used as an abrasive on sandpaper and on large tools used in machining metals, plastics, and wood. It is a black granular form of corundum, in which the mineral is intimately mixed with magnetite, hematite, or hercynite.

In addition to its hardness, corundum has a density of 4.02 g/cm3 (251 lb/cu ft), which is unusually high for a transparent mineral composed of the low-atomic mass elements aluminium and oxygen. (Full article...) -

Image 4

Graphite (/ˈɡræfaɪt/) is a crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on a large scale (1.3 million metric tons per year in 2022) for uses in many critical industries including refractories (50%), lithium-ion batteries (18%), foundries (10%), and lubricants (5%), among others (17%). Graphite converts to diamond under extremely high pressure and temperature. Graphite's low cost, thermal and chemical inertness and characteristic conductivity of heat and electricity finds numerous applications in high energy and high temperature processes. (Full article...) -

Image 5Beachy Head is a part of the extensive Southern England Chalk Formation.

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk is common throughout Western Europe, where deposits underlie parts of France, and steep cliffs are often seen where they meet the sea in places such as the Dover cliffs on the Kent coast of the English Channel.

Chalk is mined for use in industry, such as for quicklime, bricks and builder's putty, and in agriculture, for raising pH in soils with high acidity. It is also used for "blackboard chalk" for writing and drawing on various types of surfaces, although these can also be manufactured from other carbonate-based minerals, or gypsum. (Full article...) -

Image 6Deep green isolated fluorite crystal resembling a truncated octahedron, set upon a micaceous matrix, from Erongo Mountain, Erongo Region, Namibia (overall size: 50 mm × 27 mm, crystal size: 19 mm wide, 30 g)

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison, defines value 4 as fluorite.

Pure fluorite is colourless and transparent, both in visible and ultraviolet light, but impurities usually make it a colorful mineral and the stone has ornamental and lapidary uses. Industrially, fluorite is used as a flux for smelting, and in the production of certain glasses and enamels. The purest grades of fluorite are a source of fluoride for hydrofluoric acid manufacture, which is the intermediate source of most fluorine-containing fine chemicals. Optically clear transparent fluorite has anomalous partial dispersion, that is, its refractive index varies with the wavelength of light in a manner that differs from that of commonly used glasses, so fluorite is useful in making apochromatic lenses, and particularly valuable in photographic optics. Fluorite optics are also usable in the far-ultraviolet and mid-infrared ranges, where conventional glasses are too opaque for use. Fluorite also has low dispersion, and a high refractive index for its density. (Full article...) -

Image 7A ruby crystal from Dodoma Region, Tanzania

Ruby is a pinkish-red-to-blood-red-colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum (aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapphires. Ruby is one of the traditional cardinal gems, alongside amethyst, sapphire, emerald, and diamond. The word ruby comes from ruber, Latin for red. The color of a ruby is due to the presence of chromium.

Some gemstones that are popularly or historically called rubies, such as the Black Prince's Ruby in the British Imperial State Crown, are actually spinels. These were once known as "Balas rubies".

The quality of a ruby is determined by its color, cut, and clarity, which, along with carat weight, affect its value. The brightest and most valuable shade of red, called blood-red or pigeon blood, commands a large premium over other rubies of similar quality. After color follows clarity: similarly to diamonds, a clear stone will command a premium, but a ruby without any needle-like rutile inclusions may indicate that the stone has been treated. Ruby is the traditional birthstone for July and is usually pinker than garnet, although some rhodolite garnets have a similar pinkish hue to most rubies. The world's most valuable ruby to be sold at auction is the Estrela de Fura, which sold for US$34.8 million. (Full article...) -

Image 8Dolomite (white) on talc

Dolomite (/ˈdɒl.əˌmaɪt, ˈdoʊ.lə-/) is an anhydrous carbonate mineral composed of calcium magnesium carbonate, ideally CaMg(CO3)2. The term is also used for a sedimentary carbonate rock composed mostly of the mineral dolomite (see Dolomite (rock)). An alternative name sometimes used for the dolomitic rock type is dolostone. (Full article...) -

Image 9

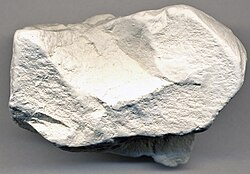

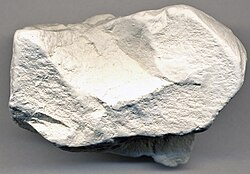

Kaolinite (/ˈkeɪ.ələˌnaɪt, -lɪ-/ KAY-ə-lə-nyte, -lih-; also called kaolin) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition Al2Si2O5(OH)4. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedral sheet of silica (SiO4) linked through oxygen atoms to one octahedral sheet of alumina (AlO6).

Kaolinite is a soft, earthy, usually white, mineral (dioctahedral phyllosilicate clay), produced by the chemical weathering of aluminium silicate minerals like feldspar. It has a low shrink–swell capacity and a low cation-exchange capacity (1–15 meq/100 g).

Rocks that are rich in kaolinite, and halloysite, are known as kaolin (/ˈkeɪ.əlɪn/) or china clay. In many parts of the world kaolin is colored pink-orange-red by iron oxide, giving it a distinct rust hue. Lower concentrations of iron oxide yield the white, yellow, or light orange colors of kaolin. Alternating lighter and darker layers are sometimes found, as at Providence Canyon State Park in Georgia, United States.

Kaolin is an important raw material in many industries and applications. Commercial grades of kaolin are supplied and transported as powder, lumps, semi-dried noodle or slurry. Global production of kaolin in 2021 was estimated to be 45 million tonnes, with a total market value of US $4.24 billion. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Tourmaline (/ˈtʊərməlɪn, -ˌliːn/ TOOR-mə-lin, -leen) is a crystalline silicate mineral group in which boron is compounded with elements such as aluminium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lithium, or potassium. This gemstone comes in a wide variety of colors.

The name is derived from the Sinhalese tōramalli (ටෝරමල්ලි), which refers to the carnelian gemstones. (Full article...) -

Image 11Quartz crystal cluster from Brazil

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical formula of SiO2. Quartz is, therefore, classified structurally as a framework silicate mineral and compositionally as an oxide mineral. Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth's continental crust, behind feldspar.

Quartz exists in two forms, the normal α-quartz and the high-temperature β-quartz, both of which are chiral. The transformation from α-quartz to β-quartz takes place abruptly at 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). Since the transformation is accompanied by a significant change in volume, it can easily induce microfracturing of ceramics or rocks passing through this temperature threshold.

There are many different varieties of quartz, several of which are classified as gemstones. Since antiquity, varieties of quartz have been the most commonly used minerals in the making of jewelry and hardstone carvings, especially in Europe and Asia.

Quartz is the mineral defining the value of 7 on the Mohs scale of hardness, a qualitative scratch method for determining the hardness of a material to abrasion. (Full article...) -

Image 12

Crystal structure of table salt (sodium in purple, chlorine in green)

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat along the principal directions of three-dimensional space in matter.

The smallest group of particles in material that constitutes this repeating pattern is the unit cell of the structure. The unit cell completely reflects symmetry and structure of the entire crystal, which is built up by repetitive translation of unit cell along its principal axes. The translation vectors define the nodes of Bravais lattice.

The lengths of principal axes/edges, of unit cell and angles between them are lattice constants, also called lattice parameters or cell parameters. The symmetry properties of crystal are described by the concept of space groups. All possible symmetric arrangements of particles in three-dimensional space may be described by 230 space groups.

The crystal structure and symmetry play a critical role in determining many physical properties, such as cleavage, electronic band structure, and optical transparency. (Full article...) -

Image 13A lustrous crystal of zircon perched on a tan matrix of calcite from the Gilgit District of Pakistan

Zircon (/ˈzɜːrkɒn, -kən/) is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is ZrSiO4. An empirical formula showing some of the range of substitution in zircon is (Zr1–y, REEy)(SiO4)1–x(OH)4x–y. Zircon precipitates from silicate melts and has relatively high concentrations of high field strength incompatible elements. For example, hafnium is almost always present in quantities ranging from 1 to 4%. The crystal structure of zircon is tetragonal crystal system. The natural color of zircon varies between colorless, yellow-golden, red, brown, blue, and green.

The name derives from the Persian zargun, meaning "gold-hued". This word is changed into "jargoon", a term applied to light-colored zircons. The English word "zircon" is derived from Zirkon, which is the German adaptation of this word. Yellow, orange, and red zircon is also known as "hyacinth", from the flower hyacinthus, whose name is of Ancient Greek origin. (Full article...) -

Image 14A sample of andesite (dark groundmass) with amygdaloidal vesicles filled with zeolite. Diameter of view is 8 cm.

Andesite (/ˈændəzaɪt/) is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predominantly of sodium-rich plagioclase plus pyroxene or hornblende.

Andesite is the extrusive equivalent of plutonic diorite. Characteristic of subduction zones, andesite represents the dominant rock type in island arcs. The average composition of the continental crust is andesitic. Along with basalts, andesites are a component of the Martian crust.

The name andesite is derived from the Andes mountain range, where this rock type is found in abundance. It was first applied by Christian Leopold von Buch in 1826. (Full article...) -

Image 15

Talc, or talcum, is a clay mineral composed of hydrated magnesium silicate, with the chemical formula Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Talc in powdered form, often combined with corn starch, is used as baby powder. This mineral is used as a thickening agent and lubricant. It is an ingredient in ceramics, paints, and roofing material. It is a main ingredient in many cosmetics. It occurs as foliated to fibrous masses, and in an exceptionally rare crystal form. It has a perfect basal cleavage and an uneven flat fracture, and it is foliated with a two-dimensional platy form.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison, defines value 1 as the hardness of talc, the softest mineral. When scraped on a streak plate, talc produces a white streak, though this indicator is of little importance, because most silicate minerals produce a white streak. Talc is translucent to opaque, with colors ranging from whitish grey to green with a vitreous and pearly luster. Talc is not soluble in water, and is slightly soluble in dilute mineral acids.

Soapstone is a metamorphic rock composed predominantly of talc. (Full article...) -

Image 16

Rutile is an oxide mineral composed of titanium dioxide (TiO2), the most common natural form of TiO2. Rarer polymorphs of TiO2 are known, including anatase, akaogiite, and brookite.

Rutile has one of the highest refractive indices at visible wavelengths of any known crystal and also exhibits a particularly large birefringence and high dispersion. Owing to these properties, it is useful for the manufacture of certain optical elements, especially polarization optics, for longer visible and infrared wavelengths up to about 4.5 micrometres. Natural rutile may contain up to 10% iron and significant amounts of niobium and tantalum.

Rutile derives its name from the Latin rutilus ('red'), in reference to the deep red color observed in some specimens when viewed by transmitted light. Rutile was first described in 1803 by Abraham Gottlob Werner using specimens obtained in Horcajuelo de la Sierra, Madrid (Spain), which is consequently the type locality. (Full article...) -

Image 17

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula CaSO4·2H2O. It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, drywall and blackboard or sidewalk chalk. Gypsum also crystallizes as translucent crystals of selenite. It forms as an evaporite mineral and as a hydration product of anhydrite. The Mohs scale of mineral hardness defines gypsum as hardness value 2 based on scratch hardness comparison.

Fine-grained white or lightly tinted forms of gypsum known as alabaster have been used for sculpture by many cultures including Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ancient Rome, the Byzantine Empire, and the Nottingham alabasters of Medieval England. (Full article...) -

Image 18

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond as a form of carbon is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of electricity, and insoluble in water. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, but diamond is metastable and converts to it at a negligible rate under those conditions. Diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any natural material, properties that are used in major industrial applications such as cutting and polishing tools. They are also the reason that diamond anvil cells can subject materials to pressures found deep in the Earth.

Because the arrangement of atoms in diamond is extremely rigid, few types of impurity can contaminate it (two exceptions are boron and nitrogen). Small numbers of defects or impurities (about one per million of lattice atoms) can color a diamond blue (boron), yellow (nitrogen), brown (defects), green (radiation exposure), purple, pink, orange, or red. Diamond also has a very high refractive index and a relatively high optical dispersion.

Most natural diamonds have ages between 1 billion and 3.5 billion years. Most were formed at depths between 150 and 250 kilometres (93 and 155 mi) in the Earth's mantle, although a few have come from as deep as 800 kilometres (500 mi). Under high pressure and temperature, carbon-containing fluids dissolved various minerals and replaced them with diamonds. Much more recently (hundreds to tens of million years ago), they were carried to the surface in volcanic eruptions and deposited in igneous rocks known as kimberlites and lamproites.

Synthetic diamonds can be grown from high-purity carbon under high pressures and temperatures or from hydrocarbon gases by chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Natural and synthetic diamonds are most commonly distinguished using optical techniques or thermal conductivity measurements. (Full article...) -

Image 19Malachite from the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Malachite is a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, with the formula Cu2CO3(OH)2. This opaque, green-banded mineral crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system, and most often forms botryoidal, fibrous, or stalagmitic masses, in fractures and deep, underground spaces, where the water table and hydrothermal fluids provide the means for chemical precipitation. Individual crystals are rare, but occur as slender to acicular prisms. Pseudomorphs after more tabular or blocky azurite crystals also occur. (Full article...) -

Image 20

Beryl (/ˈbɛrəl/ BERR-əl) is a mineral composed of beryllium aluminium silicate with the chemical formula Be3Al2(SiO3)6. Well-known varieties of beryl include emerald and aquamarine. Naturally occurring hexagonal crystals of beryl can be up to several meters in size, but terminated crystals are relatively rare. Pure beryl is colorless, but it is frequently tinted by impurities; possible colors are green, blue, yellow, pink, and red (the rarest). It is an ore source of beryllium. (Full article...) -

Image 21

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the exception of extremely rare native iron deposits, it is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth. Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, which is how ancient peoples first discovered the property of magnetism.

Magnetite is black or brownish-black with a metallic luster, has a Mohs hardness of 5–6 and leaves a black streak. Small grains of magnetite are very common in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

The chemical IUPAC name is iron(II,III) oxide and the common chemical name is ferrous-ferric oxide. (Full article...) -

Image 22

Cinnabar (/ˈsɪnəˌbɑːr/; from Ancient Greek κιννάβαρι (kinnábari)), or cinnabarite (/ˌsɪnəˈbɑːraɪt/), also known as mercurblende is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining elemental mercury and is the historic source for the brilliant red or scarlet pigment termed vermilion and associated red mercury pigments.

Cinnabar generally occurs as a vein-filling mineral associated with volcanic activity and alkaline hot springs. The mineral resembles quartz in symmetry and it exhibits birefringence. Cinnabar has a mean refractive index near 3.2, a hardness between 2.0 and 2.5, and a specific gravity of approximately 8.1. The color and properties derive from a structure that is a hexagonal crystalline lattice belonging to the trigonal crystal system, crystals that sometimes exhibit twinning.

Cinnabar has been used for its color since antiquity in the Near East, including as a rouge-type cosmetic, in the New World since the Olmec culture, and in China since as early as the Yangshao culture, where it was used in coloring stoneware. In Roman times, cinnabar was highly valued as paint for walls, especially interiors, since it darkened when used outdoors due to exposure to sunlight.

Associated modern precautions for the use and handling of cinnabar arise from the toxicity of the mercury component, which was recognized as early as ancient Rome. (Full article...) -

Image 23

Chalcopyrite (/ˌkælkəˈpaɪˌraɪt, -koʊ-/ KAL-kə-PY-ryte, -koh-) is a copper iron sulfide mineral and the most abundant copper ore mineral. It has the chemical formula CuFeS2 and crystallizes in the tetragonal system. It has a brassy to golden yellow color and a hardness of 3.5 to 4 on the Mohs scale. Its streak is diagnostic as green-tinged black.

On exposure to air, chalcopyrite tarnishes to a variety of oxides, hydroxides, and sulfates. Associated copper minerals include the sulfides bornite (Cu5FeS4), chalcocite (Cu2S), covellite (CuS), digenite (Cu9S5); carbonates such as malachite and azurite, and rarely oxides such as cuprite (Cu2O). It is rarely found in association with native copper. Chalcopyrite is a conductor of electricity.

Copper can be extracted from chalcopyrite ore using various methods. The two predominant methods are pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy, the former being the most commercially viable. (Full article...) -

Image 24

A crystalline solid: atomic resolution image of strontium titanate. Brighter spots are columns of strontium atoms and darker ones are titanium-oxygen columns.

Crystallography is the branch of science devoted to the study of molecular and crystalline structure and properties. The word crystallography is derived from the Ancient Greek word κρύσταλλος (krústallos; "clear ice, rock-crystal"), and γράφειν (gráphein; "to write"). In July 2012, the United Nations recognised the importance of the science of crystallography by proclaiming 2014 the International Year of Crystallography.

Crystallography is a broad topic, and many of its subareas, such as X-ray crystallography, are themselves important scientific topics. Crystallography ranges from the fundamentals of crystal structure to the mathematics of crystal geometry, including those that are not periodic or quasicrystals. At the atomic scale it can involve the use of X-ray diffraction to produce experimental data that the tools of X-ray crystallography can convert into detailed positions of atoms, and sometimes electron density. At larger scales it includes experimental tools such as orientational imaging to examine the relative orientations at the grain boundary in materials. Crystallography plays a key role in many areas of biology, chemistry, and physics, as well new developments in these fields. (Full article...) -

Image 25

Zeolite exhibited in the Estonian Museum of Natural History

Zeolite is a group of several microporous, crystalline aluminosilicate minerals commonly used as commercial adsorbents and catalysts. They mainly consist of silicon, aluminium, oxygen, and have the general formula Mn+

1/n(AlO

2)−

(SiO

2)

x・yH

2O where Mn+

1/n is either a metal ion or H+.

The term was originally coined in 1756 by Swedish mineralogist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, who observed that rapidly heating a material, believed to have been stilbite, produced large amounts of steam from water that had been adsorbed by the material. Based on this, he called the material zeolite, from the Greek ζέω (zéō), meaning "to boil" and λίθος (líthos), meaning "stone".

Zeolites occur naturally, but are also produced industrially on a large scale. As of December 2018[update], 253 unique zeolite frameworks have been identified, and over 40 naturally occurring zeolite frameworks are known. Every new zeolite structure that is obtained is examined by the International Zeolite Association Structure Commission (IZA-SC) and receives a three-letter designation. (Full article...)

Selected mineralogist

-

Image 1Lewis Caleb Beck (4 October 1798 Schenectady – 20 April 1853 Albany, New York) was an American physician, botanist, chemist, and mineralogist. The standard author abbreviation L.C.Beck is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[1] (Full article...)

-

Image 2

Baron Jöns Jacob Berzelius (Swedish: [jœns ˈjɑ̌ːkɔb bæˈʂěːlɪɵs]; 20 August 1779 – 7 August 1848) was a Swedish chemist. Berzelius is considered, along with Robert Boyle, John Dalton, and Antoine Lavoisier, to be one of the founders of modern chemistry. Berzelius became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1808 and served from 1818 as its principal functionary. He is known in Sweden as the "Father of Swedish Chemistry". During his lifetime he did not customarily use his first given name, and was universally known simply as Jacob Berzelius.

Although Berzelius began his career as a physician, his enduring contributions were in the fields of electrochemistry, chemical bonding and stoichiometry. In particular, he is noted for his determination of atomic weights and his experiments that led to a more complete understanding of the principles of stoichiometry, which is the branch of chemistry pertaining to the quantitative relationships between elements in chemical compounds and chemical reactions and that these occur in definite proportions. This understanding came to be known as the "Law of Constant Proportions". (Full article...) -

Image 3

Emil Wilhelm Cohen (12 October 1842 – 13 April 1905) was a German mineralogist and petrographer, born in Jutland. (Full article...) -

Image 4

Marshall McDonald (October 18, 1835 – September 1, 1895) was an American engineer, geologist, mineralogist, pisciculturist, and fisheries scientist. McDonald served as the commissioner of the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries from 1888 until his death in 1895. He is best known for his inventions of a number of fish hatching apparatuses and a fish ladder that enabled salmon and other migrating fish species to ascend the rapids of watercourses resulting in an increased spawning ground. McDonald's administration of the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries was notably free of scandal and furthered the "protection and culture" of fish species throughout the United States.

Born in 1835 in Romney, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), McDonald was the son of Angus William McDonald, a military officer and lawyer, and his wife, Leacy Anne Naylor. From 1854 to 1855, McDonald studied natural history under Spencer Fullerton Baird at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. He then attended the University of Virginia and Virginia Military Institute, from which he graduated in 1860. McDonald served as an assistant professor of chemistry at the institute under Stonewall Jackson and continued to teach intermittently throughout the American Civil War. (Full article...) -

Image 5Cecil Edgar Tilley FRS, Hon FRSE, PGS (14 May 1894 – 24 January 1973) was an Australian-British petrologist and geologist. (Full article...)

-

Image 6

John Scouler

John Scouler (31 December 1804 – 13 November 1871) was a Scottish naturalist. (Full article...) -

Image 7

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné, was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms. He is known as the "father of modern taxonomy". Many of his writings were in Latin; his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus Linnæus and, after his 1761 ennoblement, as Carolus a Linné.

Linnaeus was the son of a curate and was born in Råshult, in the countryside of Småland, southern Sweden. He received most of his higher education at Uppsala University and began giving lectures in botany there in 1730. He lived abroad between 1735 and 1738, where he studied and also published the first edition of his Systema Naturae in the Netherlands. He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala. In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals. In the 1750s and 1760s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, while publishing several volumes. By the time of his death in 1778, he was one of the most acclaimed scientists in Europe. (Full article...) -

Image 8Werner Schreyer (14 November 1930 in Nuremberg; 12 February 2006 in Bochum) was a German mineralogist and experimental metamorphic petrologist. Schreyer completed his undergraduate work in geology and petrology at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, obtained his doctorate from the University of Munich in 1957, and in 1966 received his Habilitation from the University of Kiel. He was a professor at Ruhr University Bochum from 1966 to 1996. In 2002 Schreyer became the first German to be awarded the Mineralogical Society of America's highest honor, the Roebling Medal. Schreyer was a leading expert on phase relations in the MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O (MASH) system, specializing in cordierite and minerals with equivalent chemical compositions, and high pressure and ultra high-pressure metamorphic mineral assemblages.

The mineral Schreyerite (V2Ti3O9) was named after Schreyer. (Full article...) -

Image 9

Ernest-François Mallard (4 February 1833 – 6 July 1894) was a French mineralogist and a member of the French Academy of Sciences. He is also notable for his work with Henri Louis Le Chatelier in combustion as applied to mining safety. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Johann Reinhard Blum, c. 1860

Johann Reinhard Blum (28 October 1802, Hanau – 21 August 1883, Heidelberg) was a German mineralogist.

From 1821 he studied at the universities of Heidelberg and Marburg, receiving his habilitation for mineralogy in 1828. In 1838 he became an associate professor, and in 1856, a full professor of mineralogy at the University of Heidelberg. For many years he was director of the university's mineral collection. In 1871 he was a founding member of the Oberrheinischen Geologischen Vereins (Upper Rhine Geological Association). (Full article...) -

Image 11Hans Schneiderhöhn (2 June 1887, in Mainz – 5 August 1962, in Sölden) was a German geologist and mineralogist who specialized in ore microscopy. (Full article...)

-

Image 12

Waldemar Christofer Brøgger ForMemRS FRSE (10 November 1851 – 17 February 1940) was a Norwegian geologist and mineralogist. His research on Permian igneous rocks (286 to 245 million years ago) of the Oslo district greatly advanced petrologic theory on the formation of rocks. (Full article...) -

Image 13

Johannes Martin Bijvoet ForMemRS (23 January 1892, Amsterdam – 4 March 1980, Winterswijk) was a Dutch chemist and crystallographer at the van 't Hoff Laboratory at Utrecht University. He is famous for devising a method of establishing the absolute configuration of molecules. In 1946, he became member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The concept of tetrahedrally bound carbon in organic compounds stems back to the work by van 't Hoff and Le Bel in 1874. At this time, it was impossible to assign the absolute configuration of a molecule by means other than referring to the projection formula established by Fischer, who had used glyceraldehyde as the prototype and assigned randomly its absolute configuration. (Full article...) -

Image 14

Statue of Jean-Baptiste Romé de l'Isle at the city hall of his birthplace, Gray, Haute-Saône

Jean-Baptiste Louis Romé de l'Isle (26 August 1736 – 3 July 1790) was a French mineralogist, considered one of the creators of modern crystallography.

Romé was born in Gray, Haute-Saône, in eastern France. As secretary of a company of artillery in the Carnatic Wars he visited the East Indies, was taken prisoner by the English in 1761, and held in captivity for several years. He was also an alumnus of the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris. (Full article...) -

Image 15Aristides Brezina (4 May 1848 – 25 May 1909) was an Austrian mineralogist born in Vienna.

In 1872 he graduated from the University of Tübingen, and afterwards taught crystallography at the University of Vienna. In 1878 he succeeded Austrian mineralogist Gustav Tschermak (1836-1927) as custodian of the meteorite collection at Vienna, and from 1889 until 1896 he was director of the Mineralogisch-Petrographische Abteilung (Department of Mineralogy-Petrography). In 1886, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society. (Full article...) -

Image 16Julian Royce Goldsmith (1918–1999) was a mineralogist and geochemist at the University of Chicago (Moore, 1971). Goldsmith, along with colleague Fritz Laves, first defined the crystallographic polymorphism of alkali feldspar (Newton, 1989). Goldsmith also experimented on the temperature dependence of the solid solution between calcite and dolomite (Newton, 1989). Goldsmith's research also led him to experiment with the determination of the stability of intermediate structural states of albite (Newton, 1989). For his outstanding contributions to the study of mineralogy and geochemistry, Goldsmith was awarded the prestigious Roebling Medal by the Mineralogical Society of America in 1988 (Newton, 1989). The mineral julgoldite was named for him. (Full article...)

-

Image 17Leonard James Spencer CBE FRS (7 July 1870 – 14 April 1959) was a British geologist. He was an Honorary member of the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall, and also a recipient of its Bolitho Medal. He was president of the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland from 1936 to 1939. In mineralogy, Spencer was an original investigator who described several new minerals, including miersite, tarbuttite and parahopeite. He also did important work as a curator, editor and bibliographer. He was the third person to receive the Roebling Medal, the highest award of the Mineralogical Society of America. In 1937, he was awarded the Murchison Medal of the Geological Society of London. He wrote at least 146 articles for the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.

His daughter, Penelope Spencer became a successful free-style dancer and choreographer. (Full article...) -

Image 18

Herbert Smith's refractometer

George Frederick Herbert Smith CBE (26 May 1872 – 20 April 1953) was a British mineralogist who worked for the British Museum (Natural History). He discovered the mineral paratacamite in 1906, and developed a jeweller's refractometer for the rapid identification of gems. The minerals smithite and herbertsmithite are named after him, as is Herbert's rock-wallaby. (Full article...) -

Image 19

Johann Friedrich August Breithaupt (May 16, 1791 – September 22, 1873) was a German mineralogist and professor at Freiberg Mining Academy in Freiberg, Saxony. (Full article...) -

Image 20

Ernst Friedrich Germar (3 November 1786 – 8 July 1853) was a German professor and director of the Mineralogical Museum at Halle. As well as being a mineralogist he was interested in entomology and particularly in the Coleoptera and Hemiptera. He wrote monographs on several insect families including the Scutelleridae. He also took an interest in paleoentomology. (Full article...) -

Image 21

Joan Abella

Joan Abella i Creus (Sabadell, Barcelona, 1968) is a Catalan gemmologist and mineralogist who discovered abellaite, a mineral that receives this name in his honor. (Full article...) -

Image 22Gold and Diamonds - from John Mawe's 1812 book Travels in the Interior of Brazil

illustrated by James Sowerby

John Mawe (1764 – 26 October 1829) was a British mineralogist who became known for his practical approach to the discipline. (Full article...) -

Image 23

Charles Palache (July 18, 1869 – December 5, 1954) was an American mineralogist and crystallographer. In his time, he was one of the most important mineralogists in the United States. (Full article...) -

Image 24Portrait by John Opie c1795

Philip Rashleigh FRS FSA (28 December 1729 – 26 June 1811) of Menabilly, Cornwall, was an antiquary and Fellow of the Royal Society and a Cornish squire. He collected and published the Trewhiddle Hoard of Anglo-Saxon treasure, which still gives its name to the "Trewhiddle style" of 9th century decoration. (Full article...) -

Image 25

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the greatest and most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on literary, political, and philosophical thought in the Western world from the late 18th century to the present. A poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre-director, and critic, his works include plays, poetry and aesthetic criticism, as well as treatises on botany, anatomy, and colour.

Goethe took up residence in Weimar in 1775 following the success of his first novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), and joined a thriving intellectual and cultural environment under the patronage of Duchess Anna Amalia that formed the basis of Weimar Classicism. He was ennobled by Karl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar, in 1782. Goethe was an early participant in the Sturm und Drang literary movement. During his first ten years in Weimar, Goethe became a member of the Duke's privy council (1776–1785), sat on the war and highway commissions, oversaw the reopening of silver mines in nearby Ilmenau, and implemented a series of administrative reforms at the University of Jena. He also contributed to the planning of Weimar's botanical park and the rebuilding of its Ducal Palace. (Full article...)

Related portals

Get involved

For editor resources and to collaborate with other editors on improving Wikipedia's Minerals-related articles, see WikiProject Rocks and minerals.

General images

-

Image 1An example of elbaite, a species of tourmaline, with distinctive colour banding. (from Mineral)

-

Image 2Perfect basal cleavage as seen in biotite (black), and good cleavage seen in the matrix (pink orthoclase). (from Mineral)

-

Image 4Mohs Scale versus Absolute Hardness (from Mineral)

-

Image 5Muscovite, a mineral species in the mica group, within the phyllosilicate subclass (from Mineral)

-

Image 6Asbestiform tremolite, part of the amphibole group in the inosilicate subclass (from Mineral)

-

Image 8Schist is a metamorphic rock characterized by an abundance of platy minerals. In this example, the rock has prominent sillimanite porphyroblasts as large as 3 cm (1.2 in). (from Mineral)

-

Image 12Native gold. Rare specimen of stout crystals growing off of a central stalk, size 3.7 x 1.1 x 0.4 cm, from Venezuela. (from Mineral)

-

Image 13Black andradite, an end-member of the orthosilicate garnet group. (from Mineral)

-

Image 15When minerals react, the products will sometimes assume the shape of the reagent; the product mineral is termed a pseudomorph of (or after) the reagent. Illustrated here is a pseudomorph of kaolinite after orthoclase. Here, the pseudomorph preserved the Carlsbad twinning common in orthoclase. (from Mineral)

-

Image 17Red cinnabar (HgS), a mercury ore, on dolomite. (from Mineral)

-

Image 18Diamond is the hardest natural material, and has a Mohs hardness of 10. (from Mineral)

-

Image 19Pink cubic halite (NaCl; halide class) crystals on a nahcolite matrix (NaHCO3; a carbonate, and mineral form of sodium bicarbonate, used as baking soda). (from Mineral)

-

Image 20Mohs hardness kit, containing one specimen of each mineral on the ten-point hardness scale (from Mohs scale)

-

Image 22Epidote often has a distinctive pistachio-green colour. (from Mineral)

-

Image 23Hübnerite, the manganese-rich end-member of the wolframite series, with minor quartz in the background (from Mineral)

-

Image 24Gypsum desert rose (from Mineral)

-

Image 26Sphalerite crystal partially encased in calcite from the Devonian Milwaukee Formation of Wisconsin (from Mineral)

Did you know ...?

- ... that leonite (pictured) has been found on Mars?

- ...that crystals of Paulingite, a rare zeolite mineral found in vesicles in the basaltic rocks from the Columbia River, form a perfect clear rhombic dodecahedron?

- ... that abernathyite is both fluorescent and radioactive and is named for the mine operator who discovered it?

Subcategories

Topics

| Overview | ||

|---|---|---|

| Common minerals | ||

Ore minerals, mineral mixtures and ore deposits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ores |

| ||||||||

| Deposit types | |||||||||

| Borates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonates | |||||

| Oxides |

| ||||

| Phosphates | |||||

| Silicates | |||||

| Sulfides | |||||

| Other |

| ||||

| Crystalline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptocrystalline | |||||||

| Amorphous | |||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||

| Notable varieties |

| ||||||

| Oxide minerals |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicate minerals | |||||

| Other | |||||

Gemmological classifications by E. Ya. Kievlenko (1980), updated | |||||||||

| Jewelry stones |

| ||||||||

| Jewelry-Industrial stones |

| ||||||||

| Industrial stones |

| ||||||||

Mineral identification | |

|---|---|

| "Special cases" ("native elements and organic minerals") |

|

|---|---|

| "Sulfides and oxides" |

|

| "Evaporites and similars" |

|

| "Mineral structures with tetrahedral units" (sulfate anion, phosphate anion, silicon, etc.) |

|

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

References

- Pages with Swedish IPA

- Pages using Template:Post-nominals with customized linking

- Manually maintained portal pages from May 2019

- All manually maintained portal pages

- Portals with triaged subpages from May 2019

- All portals with triaged subpages

- Portals with named maintainer

- Automated article-slideshow portals with 31–40 articles in article list

- Automated article-slideshow portals with 201–500 articles in article list

- Portals needing placement of incoming links